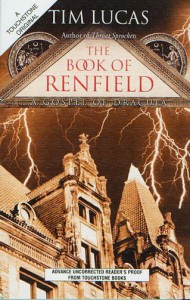

THE BOOK OF RENFIELD is quite a genetic experiment. Tim Lucas took Stoker’s Dracula DNA and turned it into material for a test tube. He put it under the lenses of a lab microscope and he contaminated, hybridized and blended it with new material, with a substance of uncertain composition which changed its colors, but kept its deeper texture intact.

THE BOOK OF RENFIELD is quite a genetic experiment. Tim Lucas took Stoker’s Dracula DNA and turned it into material for a test tube. He put it under the lenses of a lab microscope and he contaminated, hybridized and blended it with new material, with a substance of uncertain composition which changed its colors, but kept its deeper texture intact.

As a new architect of new organisms, the writer seems like a botanist looking for new plant varieties. He works as a geneticist who finalizes interbreeds, searching for a new reality.

The archetypes of the story remain the same while the narrative structure is filled with echoes, suggestions and reflections.

Dracula speaks to the new generations, but his voice is placed inside a vast, empty cathedral which reverberates its sound, multiplying it indefinitely. So we discover new harmonics (some higher, others lower) under his voice – a voice we learned to love with its terrible admonishing tone.

Everything is seen through Renfield’s colored lens. He may be just a minor Stoker’s character , but he truly is one of the most compelling.

To Stoker, this character was quite a secret admonition of how permeable to evil the Victorian society was. Renfield is “the madman”, but there is a method in his craziness which is the fruit of a logical and rigid chain of causes and effects. The Victorian audience looked at Renfield with some sense of horror, but what it discovered right in his eyes was, above all, the subversion of its own values. Locked into the madhouse, Renfield was exactly what everyone could have been if only one had allowed his Es to overtake the reason of one’s SuperEgo. Renfield was seen as something to hold at a distance, to keep in an appointed place of psychological removal. The danger he represents has nothing to do with the fact that he may harm you, but it depends on the fact that he warns you, on the fact that he tells you that you can become exactly what you try to avoid.

For this reason Renfield, in Stoker’s novel, is quite a miniature Dracula. He has no noble titles, but he desires immortality; he doesn’t drink blood, but he feeds on animals. And he chooses, among all possible living creatures to eat, just the invisible ones, the ones which are deeply hated by all the social forum: the flies fed with garbage, and the rats which are a powerful symbol of sexual promiscuity and of dirty bestiality. In religious paintings rats are often the eaters of the roots of the Tree of Life.

Yet this pregnant reality is filled with shadows when the story goes from the novel to the screen. To Murnau, for example, Renfield (who, at the beginning, is not in the madhouse, but is a realtor – you can say that he inhabits society, and in fact he sell houses) has quite the same importance of the vampire. He is the bridge which connects the land of the phantasms (you can say our subconscious and our libido) with our civilized world. He reads hieroglyphs and turns them into notary deeds. And when the vampire dies it is he who descends into the grave, and is lynched by the crowd because he dared get out of the madhouse in which he had been conveniently confined. He is terrible for he is our relative. In his veins flows the same blood which flows in ours.

In Lucas’ novel the theme is conjugated in a different way. Renfield is a subverted child. The fact that he had no mother locks him in a psychic labyrinth with no way out. Dracula is his Minotaur, while Mina is his wirekeeping Arianna. But to get out of this labyrinth is to lose himself. The price is death and nothing else.

As a child he cannot go further than the oral phase of personality development. His sexuality is confined to the desire of a female breast to drink from, and feeding with animals is to him a real abjection because he loved animals and was reciprocated by them. Animals are to him in any case a surrogate of milk more than of blood.

This is where that Lucas’ novel is most innovative. Vampirism is shown in its most terrible and rotten dimension. If, as many critics agree, vampirism is a manifestation of sexual frustration in which the monster replaces penetration with a bite, to Lucas it is the expression of some kind of subtler perversion which changes form according to the person in front of him. Four faces, we are told, but they change every time and the change depends on the person who reflects his own image in it. In this perspective the finale makes more sense, with its transposition to our times and the tragedy of 9/11. Not only for the fact that the vampire’s myth and archetype are upgraded to contemporary politics, but above all for the fact that the novel itself becomes matter of discussion and of comprehension of the entire contemporary society. The essayist and the sociologist join hands with the novelist and the anthropologist to put the novel in front of a new mirror, or to submerge it in dye which puts in light (or in shadow) new landscapes.

The novel is, for this reason, an operation of rewriting on a rereading. The entire first part of the novel is wonderfully functional to this spirit, and it is so because it is faithful to the original novel while it paradoxically distances itself from its words. The infinitely far is infinitely close when we use the right tools.

Pity then that just in the pre-finale, that is to say in the moment in which the story falls in the “already told” of Stoker’s Dracula, Lucas’ writing gets more mechanical and less original.

But it’s a venial sin for an intensely new novel.

Il sito personale di Alessandro Izzi